Browsing the library orchard at Riley’s Cidery

Written by Katie Selbee

Even Gulf Islanders have to grudgingly admit that the view of coastal mountains, islands and sea at the Horseshoe Bay ferry terminal west of Vancouver is unbelievably idyllic. It’s from here that you can look out and spot the forested outline of Nex̱wlélex̱wem, as traditionally named by the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish) Nation, also known as Bowen Island to settlers, only a 20-minute sail from the shore.

Christine Hardie and Rob Purdy and their two young kids had already been living on the island for years when they connected with a retired couple, Josephine and John Riley, and decided to start a cidery here. The Rileys were hoping to move on from an impressive 30-year horticultural passion project—what is likely the most genetically-diverse apple orchard in the country—and sell the acreage to someone who would continue to steward it. Having a background in sustainable farming, Christine immediately took an interest.

Over the next two years, she and Rob began helping John around the orchard; in turn, John taught Christine the ropes of apple tree care and the origin stories of each tree. Eventually, the Rileys sold the property to the couple and left, and Rob and Christine moved onsite and began the work of converting the barns and out-buildings to a cidery in partnership with friends and investors. They released their first ciders last summer, 2021.

As we walk through the gate and down into the main orchard, I spot handwritten name-tags neatly hanging on each tree. Christine explains that almost every single tree in the main orchard (nearly 1000) is a different variety, which means the harvest window is different for each. To further complicate things, the trees were planted whenever John Riley obtained the scionwood over the course of decades, so it is no easy task to locate which varieties are ripe when harvest season rolls around. Christine laughingly admits that it’s a commercial grower’s nightmare, but luckily, cidermaking allows more flexibility: they can typically wait until the fruit drops to collect it, which would be past prime if they were harvesting apples for fresh-eating use, but it’s the perfect ripeness for cidermaking.

The dwarf-rootstock orchard has been trained cordon style, and the tightly-spaced rows are horizontally terraced down a slope, making it feel more like a plant labyrinth than an orchard block. At no point can you get a full view of the planting as a whole, as the apple tree rows are woven around various ponds, bubbling waterways, potting sheds and lined garden beds containing nearly 100 species of rhododendrons, a tall witch hazel, grape vines, quince, pear (including old perry-specific varieties), nut and peach trees, blueberries, and countless other plants.

A newer section of orchard with semi-standard, cider-specific varieties.

Some of the trees and plants are decades old and others just a few years: as Christine explains, John “went on this planting rampage before he left, just trying to get it finished.” Walking around, each tree is neatly labelled and you see names like Granniwinkle, Arlingham Schoolboys, Paula Red, Mother.

I couldn’t help asking Christine a question that has haunted my mind ever since we planted an espalier orchard amidst a forest of fir trees: what if a tree falls on the trellis lines and wipes out some of the rarest varieties? Christine laughs, “I think of that all the time!”. And that’s part of the reason why she’s eager to see this library orchard propagated beyond their cidery—to make sure the genetic and taste diversity is not just preserved here but actively used for grafting and learning. The Riley’s living collection is well known in the botanical world, with places like VanDusen Garden in Vancouver already having established a small orchard from some of their cuttings.

Rob also tells us that two years ago, they had 80 of the most famous and oddball table varieties grafted onto about 1000 rootstock, and then offered them for sale to the public. “We sold about 800 trees,” he says, “which went mostly to locals around Bowen Island.” They were amazed by how many locals became apple growing enthusiasts when offered these fascinating, obscure varieties—some folks with limited green space were even planning to container-grow the trees on balconies.

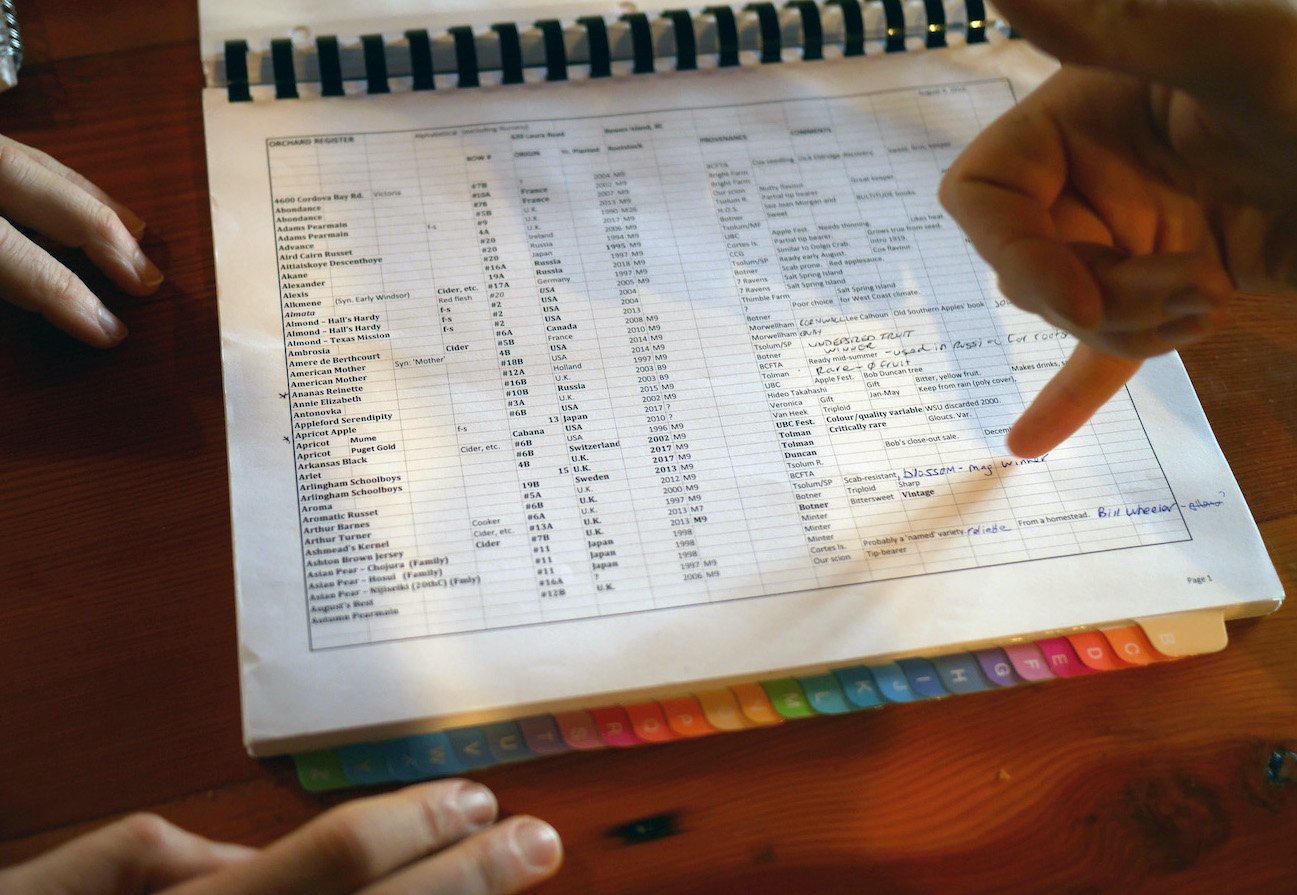

Part of Christine's work with John Riley was cataloguing each of the near-1000 varieties and sources of each original piece of scion wood.

When we flip through the alphabetized index of varieties, the scionwood sources read like a Who’s Who of apple preservation pioneers from the UK to Maine State to Cortes Island. We even spot “Tsolum River” among the list: a nursery we’ve come across in our own research, started by artist Renée Poisson on Vancouver Island in the 1980’s. She propagated over 350 rare varieties and was one of few sources for antique varieties in Canada at the time.

We wind our way out of the orchard and up to the production space. Large stainless tanks flank the outside of the building, and Christine explains that because floor space is limited, the cidermaking process is always a bit of a logistical shuffle. Like with our own production, bottling has been happening throughout the year instead of one set span of time. For a mix of reasons, she finds herself leaning towards doing primary fermentation in barrels (favouring its subtlety over lengthier barrel aging), as well as the charmat method of naturally-conditioning a cider in a pressure-rated tank before bottling it (as opposed to in-bottle conditioning).

Christine’s technical training for both farm and cider overlaps with our own—she took the same cidermaking course with Peter Mitchell that Matthew completed (not coincidentally, as it is still one of few courses available globally) and she and Rob toured Herefordshire cideries like Tom Oliver’s to gain a better understanding of traditional English cidermaking. Years before that, she was in the same cohort as me (Katie) when I completed the UBC Farm’s practicum in sustainable agriculture in 2013, which is where we first met…back when both of us still had organic vegetable farming on the brain. Now we can’t help joking about how, of the 9 practicum students that year, 4 of us now operate craft alcohol productions: ourselves along with Diana at Callister Brewing and Fabio at Woods Spirits. Which perhaps tells you more about the realities of organic vegetable production than it does about craft booze.

Long Lost Apples contains the majority of the many hundreds of diverse varieties from the Riley Orchard.

Flipping to the present, like the majority of BC cideries, Christine and Rob’s ciders are a mix of the fruit from their own orchard (including the quince) and apples they source from the interior. Their main source is a now-retired farmer, Doe Gregoire, whom they connected with through a friend. She was one of the first certified-organic apple growers in the Similkameen Valley, back in the 1988 establishing an orchard entirely of McIntosh apples (basically the polar opposite of the Riley’s orchard). The “Mac,” a variety first discovered as a chance-seedling in 1811, had a firm hold as the most popular variety in commercial apple production across Canada for some time. In recent decades, the BC fruit market has moved on from the Mac, which was praised as an ideal mixed-use apple, to varieties that have been bred to taste sweeter—more suitable for fresh-eating purposes—and less prone to bruising, like the Gala.

As Doe Gregoire explained later via email, she has ‘seen many varieties come and go usually to please the ever-changing tastes of the consumer, which in turn has a direct effect on the price of the apple. To this end, farmers will continuously take out one variety for another accordingly. This change is more economical and easily done when you are using Super Spindle root stock, since the trees can produce fruit within the second year of planting compared to the eight-year wait with standard rootstock.’

At Doe’s orchard, Four Winds Farm, the trees are on a standard size root stock, a Russian type named Antonovka. It’s very cold hardy and can produce fruit for upwards of eighty years. Larger trees like this also have a canopy protecting the apples from sun scald and light hail. Because of this, Doe has decided to keep standard trees and not replant with high-density rootstock. Doe added, ‘The yield in comparing the two types of growing is equal, but the difference is increased labor intensity with the larger trees. Having said this, my decision to stay with growing Macs has been good as the supply and demand of the apple have had farmers replanting the Macs once again after taking them out for the Gala which lost favour in the fresh market place in more recent times.’

Her decision not to switch from Macs has been an unexpected bonus for Christine and Rob, whose cidery has given new relevance and value to this orchard. And they’re finding the humble Mac to be a surprisingly good apple for cider use, since their single-variety organic Mac cider won a gold medal in the 2021 International Cider Awards.

As year one of being open to the public comes full-circle, Rob and Christine say they’re gratified by the enthusiastic support of Bowen islanders and the many Vancouver tourists who frequent the island. The cidery’s beautiful rock-walled patio area (which took 6 months for a masonry friend to build) has already become a local hangout. The local-centric consumer base has also enabled them to reclaim many of their glass bottles for washing and re-use over this past year—which despite requiring significant time and labour, greatly reduces their packaging footprint.

Between themselves (both working other jobs on the side), their cidery helpers Frank and Isaac, various WWOOFers who have come and gone, and regular phone calls with John Riley, they are cultivating their own niche in the BC cider industry (which uniquely involves turning local cider drinkers into backyard apple growing enthusiasts). And we’re so happy they’re here.

You can find Riley’s Cider on their web shop and local stockists, and on IG.